After the 2014 Lok Sabha elections in India, a right-wing Hindu political party, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), came to power at the national level. Over the last nine months, the new government has stridently tested the waters to see how far it can push its political ideology - Hindutva – an ideology that rests on paternalistic Hindu discourse with some free market chest thumping combined with a fractured articulation of poverty, marginalization and the plight of minorities. The tests have come in little doses. First, ancient Indian culture has been constructed as more progressive than historians’ claims to the contrary. So the myth about a poor graft of an elephant’s head on the son of a god who accidentally lobbed it off, was seen as evidence of how India had invented plastic surgery. Similarly, according to the right wing, flight was invented in India although without a proper discussion of aerodynamics. A few months later, two religious leaders advised Hindu women to have 4 and 10 children respectively, with most children being given into the service of the nation. During the Obama visit in January 2015, the Preamble to the Indian Constitution was served up in its original form, where the words “socialist” and “secular” do not appear, being later additions to the Preamble.

Since the Bharatiya Janta Party (BJP) government has come to power (and even before) there has been a sharp increase in informal edicts being issued to govern social behavior. Couples were asked by the Hindu Mahasabha to not frolic on Valentine’s Day or else they will be forcibly married off. Comedy Central was taken of the air in India for being “offensive” and a Comedy Central style “roast” was pulled off YouTube for being vulgar and obscene. First Information Reports have been recently filed against the organizers of the roast. Activists that blamed the Modi-led government in Gujarat during the 2002 riots that targeted Muslims, like Teesta Setalvad, have recently found themselves in a legal nightmare. On the other hand, 70 people charge sheeted in the riots, were acquitted.

Since the Bharatiya Janta Party (BJP) government has come to power (and even before) there has been a sharp increase in informal edicts being issued to govern social behavior. Couples were asked by the Hindu Mahasabha to not frolic on Valentine’s Day or else they will be forcibly married off. Comedy Central was taken of the air in India for being “offensive” and a Comedy Central style “roast” was pulled off YouTube for being vulgar and obscene. First Information Reports have been recently filed against the organizers of the roast. Activists that blamed the Modi-led government in Gujarat during the 2002 riots that targeted Muslims, like Teesta Setalvad, have recently found themselves in a legal nightmare. On the other hand, 70 people charge sheeted in the riots, were acquitted.

On a more policy-oriented scale, bills pending in the Lok sabha include bills that will substantially dilute the rights of many people. The new proposed Land Acquisition Act will impinge on the rights of forest dwellers and an amendment to the Medical Termination of Pregnancy Act will allow (if passed) practitioners of alternative medicine systems – Siddha, Ayurveda, Unani and Homeopathy– to perform abortions up to a period of 24 weeks into a pregnancy.

All of this has caused great concern to many ordinary Indians. However, the BJP won a plurality in the Lok Sabha with 282 seats, but got only 31 percent of the vote share. With 282 seats, it did not need any coalition partners that could possibly have tempered some of the stranger policy planks. Added to this, Prime Minister Modi spent most of his first six months in office taking foreign tours in order to build diplomatic relations with several countries.

There is no doubt amongst many of the liberal elite in India that the Indian electorate is being pushed to see how much cultural and policy change it will tolerate without popular dissent. Mr. Modi, since assuming office, has kept himself aloof from party politics, leaving the nitty-gritty of organizing a party to his faithful deputy, Amit Shah, who was, not so long ago, implicated in the fake encounter killing of Ishrat Jahan. He has since been cleared of all charges.

It is in light of these changes that have occurred in the Indian political and public sphere that we need to look at the New Delhi assembly elections that ended on Feb 10. Now, during the Lok Sabha election last year, the BJP did rather well in New Delhi. However, they were unable to translate their popularity in New Delhi to an electoral win in the assembly polls earlier this month. Primarily, as many have argued, this was because of the timing of the elections. By waiting until 2015 to hold elections to the New Delhi assembly, the BJP allowed its chief contender (that had been written off by most), the Aam Aadmi Party (AAP) to regain ground that they had lost after a disaster of a minority government that lasted 49 days between the end of 2013 and early 2014.

The New Delhi assembly elections are significant because this is the first time that the BJP has so decisively lost an election in any part of India, and that too amongst people that voted for it in the last Lok Sabha election. It even gained ground in the contested state of Jammu and Kashmir, where it won 25 out of 87 seats mostly prompted by voting in the Jammu region, which has traditionally been a stronghold of Kashmiri Hindus. The Kashmir Valley, however, voted differently.

This is why the New Delhi assembly elections are important. This is the first election where the BJP has lost decisively leading one commentator to suggest that Delhi is like Gaul from the Asterix comic books – with Asterix (Arvind Kejriwal) standing up to Caesar (Modi). I

n this election, the AAP not only recovered lost ground, it knocked all other competition out of the playing field. The AAP won 67 out of 70 assembly seats and trounced the BJP and its chief candidate, Kiren Bedi, a former police officer with an exemplary service record, but a rather checkered record in public life.

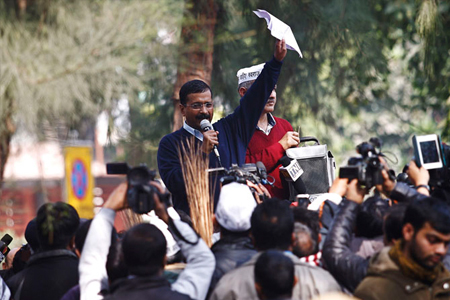

So how did the AAP win this election? One of the things that has always stood out amongst the AAP leaders and their cadres, as I found out when I covered their campaign in rural Mewat district of Haryana last year, is that they are a no frills set-up. They are humble and instead of summoning crowds to an organized rally, they go to the most interior places and speak under trees. In urban areas, AAP candidates went house to house and canvassed for votes. This time, they went house-to-house and apologized for making a mess of things during their 49 days in office. More specifically, they apologized for not taking the public’s opinion into account while offering the resignation of their government.

What seemed like a terrible decision last February, to leave the Delhi assembly and go national, now seems to have been a political masterstroke. The AAP did poorly in the Lok Sabha elections winning only 4 seats (mostly in Punjab). Since then, there were rumors of party infighting and some of their stalwarts, like Shazia Ilmi, left and defected to the BJP. The AAP is a unique party in Indian politics precisely because it does not have a clear ideological plank. This oddly has turned it into a clear catchall party.

The AAP emerged in 2012 from a mass movement that was broadly called India Against Corruption (IAC). IAC was launched by Anna Hazare, a Gandhian stalwart, who, sickened by corruption in the public sphere and government, decided to go on an indefinite hunger strike to fight for the passage of the Jan Lokpal Bill. The bill was supposed to create the post of a ombudsman who would look into allegations of public corruption.

Arvind Kejriwal was an ally of Anna Hazare, until the point where the two fell out over the direction of the movement. Kejriwal wanted an institutionalized fight against corruption, while Hazare preferred the mass agitation route. What emerged under Kejriwal’s leadership was the Aam Aadmi Party. For a while the AAP flirted with competing ideologies, both the right and the left, but managed to steer clear of affiliating itself with either. Instead, its ideology emerged as a form of morality to be practiced in public life. The party revealed all details of its donations, created an internal party ombudsmen to look into charges against its own candidates, and stood out clearly from other parties for literally practicing what they preached.

In doing so, as Rahul Verma and I have argued, the AAP created a space for a discussion for institutional transformation in Indian politics aimed at making things less murky. We also argued that many parties that start out like the AAP (case in point being the Bahujan Samaj Party), often may not be able to live up to those high standards they set because they cannot really control the actions of individual candidates to the highest degree. Even so, we said, by opening up a public debate on the need for transparency in many spheres of electioneering and public office, the AAP single-handedly has managed to change some rules of the game.

It is hard at this point to refrain from drawing a comparison between Delhi and dirty Gotham City, where Batman cleans up the streets, brings crooked cops to justice and fights the bad guys. Kejriwal has been referred to as “Muffler Man”, because of his characteristic fashion – sweater, trousers, sneakers and the AAP cap accompanied by a muffler around his neck during the winter. That is quite an unassuming superhero (no gadgets and super car), but to many he is someone who has beaten the odds.

So who sees him as a savior and why did they vote for him? While there is still some data to be collected on the social profile of the voters, Yogendra Yadav of the AAP, suggested that overwhelming support for the AAP and Kejriwal came from the urban poor in Delhi. Now these voters may have been those who voted for the Congress in previous elections, but following the party’s decline over the last year, they essentially switched their votes to the AAP.

However, what is interesting is that the AAP also won in zones where during the Lok Sabha election people voted for the BJP. What this possibly tells us is that voters are discrete about their preferences. They have chosen one ideology at the national level, but at the local level their electoral preferences have evolved to the point where ideology may matter less than efficient delivery of public goods, which the AAP has promised. However, as Gilles Vernier has pointed out, what we should be looking at is how the BJP fares in a bipolar contest (apparently not so well), and, the swing votes that favored the AAP.

The AAP’s victory must be seen as a cluster of things. First, nothing beats the benefit of having a cadre-based party where volunteers canvass door-to-door and create real links with voters, instead of summoning them to hear speeches. Second, voters, especially poor ones and minority voters, seem to have seen through the doublespeak of the right wing – promising protection on the one hand, while on the other, right-wing groups ban films, attack people, burn books and so on. Third, for poor voters, what the AAP promises is not just development (technically targeted at the already upwardly mobile), but development with some equality and dignity. Finally, the AAP’s win does restore some faith that positive institutional change is possible and it will be electorally supported by people.

Vasundhara Sirnate is the Chief Coordinator of Research at The Hindu Centre for Politics and Public Policy, located in Chennai, India. She is also a Ph.D student at the Travers Department of Political Science, Berkeley.